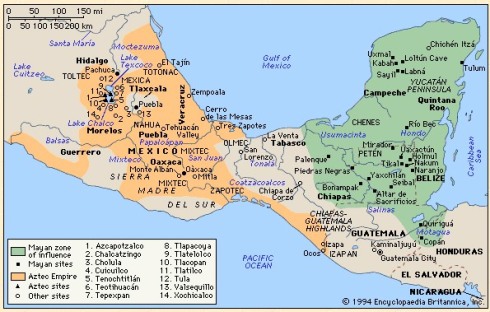

Ancient Mexican culinary history began about 9000 years ago, around 7000 BCE, when the Mayan culture occupied the areas we now call Belize, Guatemala and Ecuador where it reached its apex from 300 to 1000 CE. The culture then moved to the Yucatan peninsula, perhaps because they had run out of trees to burn in the making of limestone stucco/cement for building, where the empire again attained amazing levels of sophistication. Between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries deforestation, drought and 100 years of civil war reduced the Mayan to a dynasty easily conquered by the Spanish who mixed their cuisine with that of the local foodways to begin the history of Mexican food. The food of the ancient Mayan, Mixtec, Olmec, Toltec, Inca, and Aztec, although separated by time and distance, all existed within in a common agricultural universe cross fertilized by centuries of conquest and commerce that formed Mexican cuisine as we know it today.

MEXICAN COOKING TERMS translated to English … read more, click here

VIEW Diego Rivera’s watercolors on a Mayan Theme Nice series of seven.

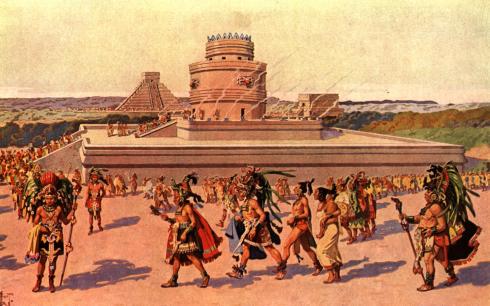

An artist rendering of a Mayan city

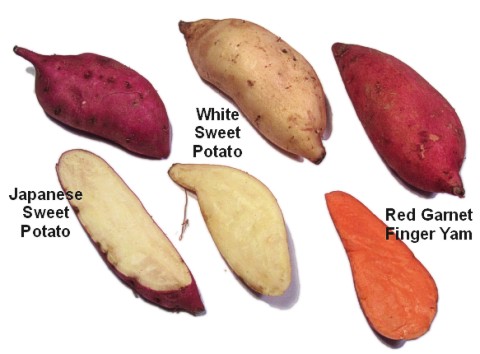

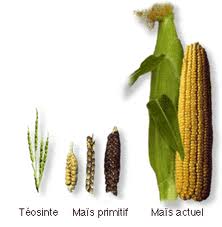

Camotes or sweet potatoes, have long-held a place in the Mexican diet, first grown in Peru around 8000 BCE, they still provide a notable source of protein for the poor of both the new and old worlds. The early cultures of the lower Americas, except for the nobility, relied on the extensive use of wild corn/teosinate, vegetables, an occasional insect, a handful of maguey/agave cactus grubs, a little jungle protein and perhaps a fish or two if you lived near the water. The only domesticated protein sources were turkeys, doves, Muscovy ducks that nested in trees, several Chihuahua like and the hairless Xoloitzcuintli … Zolo for short … dog. Early Mexican Mesoamerican food history tells us that chilies were common by 7200 BCE, squash around 4000 BCE and the oldest non-teosinate corn samples, from the Ladrones cave in Panama, have been dated to 3500 BCE with cultivation occurring around 2000 BCE. Around the same time period maize, breadfruit and cassava were processed into masa one of the historical foundation foods of Mexican and Mesoamerican cuisine. Recent discoveries suggest that many of these items were cooked by adding heated clay balls to the cooking vessel much like early Europeans used heated rocks.

Mexican Mesoamerican cuisine is rife with indigenous cultivars that include amaranth, chia, avocado, cassava, guava, mombiu, nance, pineapple, sapodilla, sweet potatoes (4 types), yucca, chocolate, marmay, zapote. and cherimoya. Mexican cuisine has long featured beans like navy, Lima, wax, pinto black and scores of others that were cooked with epazote and chilies, and appeared at almost every meal. Any survey of Mexican food would be incomplete without mentioning a wide range of squashes and their seeds, added to masa or other constructs to flavor and thicken. The leaves of these cultivars were and still are used to wrap other vegetables or protein in masa and then steamed or fire roasted. Squashes were often cooked in maguey syrup and the blossoms when stuffed were wrapped in masa and steamed. Dried gourds were used as storage containers or vessels and during battles, filled with embers and chilies, wrapped in leaves or cotton material, and then hurled at the enemy as ballistics of chemical warfare. And finally a bad little Mexican child could be punished by being held and smoked over one of these same devices until they cried. Many of these historic Mexican food cultivars, although unknown to us in our world, are still eaten in rural areas where subsistence farming is the norm and will never leave since they are far too perishable to transport more than a few miles. Depending on the area many American tubers and roots were also a staple of both the Aztecs and the Mayan.

THE HOTTEST CHILI PEPPER IN THE WORLD … read more, click here

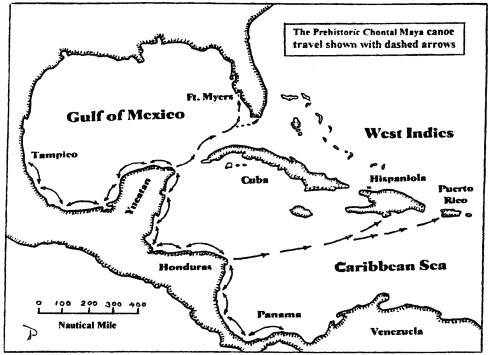

The Mayan move to the jungle meant that the nobility now had access to deer, iguana, monkey, armadillo, peccary, agouti, and the boar like javelina in addition to the Muscovy duck, turkey and the canine Xoloitzcuintli and Chihuahua dogs which they had dined on since 5500 BCE. The ranching of these dogs was a lucrative and esteemed middle class occupation in Mexican food history. These dogs, fed a diet of avocados and maize, were slaughtered before their first birthday much like our modern-day veal. Their descendants, long thought extinct, were found in the interiors several decades ago and now they are a sanctioned breed of the Mexican equivalent of the AKC. New Mayan settlements on the coast constructed large seagoing canoes becoming the Phoenician traders of the New World and engineered a magnificent system of roads and bridges for inland trade with centers like Chichen Itza and Teotihuacan.

Mayan Gods … read more, click here

An estimated 200 plus insects varieties were and, in many cases, still are consumed by both ancient and current day Mexicans. This wealth of insects, with protein levels ranging from 10 to 80%, includes the raw or cooked adult, eggs, pupae and larvae of hundreds of regional types. This entomophagic menu lists such house specialties as wasps, grasshoppers, dragon-fly larva, bees, flies, lice, months, butterflies and caterpillars, worms, water bugs, cicadas and beetles. This huge protein resource combined with fresh and/or salt water turtles, crocodiles, caiman, bull sharks, fish and snakes had nutritional significance for the diminutive sized Mexican or Mayan peasant who was often a foot shorter than the well fed ruler, priest or warrior and insects are still a major dietary player in some of the rural parts of Mexico today.

A Modern Xolo whose ancestors were a major protein source

Since little harvestable mass could exist on the forest floor, because most of the nutrients of the jungle supported the tall trees of the canopy, the Mayans augmented their diet with any other protein available. Maize, beans, chia, and amaranth were the cornerstones of Mexican food history and when combined with a few ants, some sting-less bees, and maybe a couple of beetles they provided a tasty and nutritionally balanced low-calorie meal. Bishop Diego de Landa in the sixteenth century reported that the Maya women in the Yucatan would:”raise other animals and let the deer suck their breasts, by which means they raise them and make them so tame so they will never go into the woods.”Mayans of the sixteenth century consumed only 1200 calories a day; that’s malnutrition by today’s standards. Their European counterparts wolfed down about 1800 and the average American today consumes a paltry 2400. Yes, this diet made for some pretty small people who were still able to build some pretty big structures, create an admirable astrological theory and established a trade network that stretched to the North American Southwest to create the history of Mexican food; a true mother cuisine.

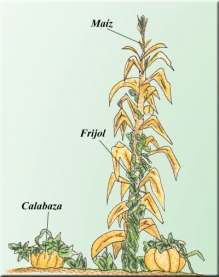

The Pre-Columbian cuisines of Mesoamerica and Mexican food both owe their success to maize, nixtamalization and milpas. The cuisine of Mexico has long relied on the milpa or mixed crop method that planted corn, beans, squash, and other cultivars (usually chilies) in the same rather small field. This technology meant that the same crops could be planted over and over without depleting the soils nutrients because the joint plantings enriched the soil in an amazingly symbiotic way. This selective planting reduced herbivore infestations, enriched the soil with nitrogen and allowed multiple dietary components to be cultivated and harvested with little labor. Both the Aztecs and the Mayan used the milpa farming system where herbs, chilies, squash, beans, and corn created their own mutually beneficial universe. The beans would support the cornstalks and add nitrogen to the soil, the large leaves of the squash would help to conserve moisture by shading the root system, and the chilies and herbs provided some deterrent to animals and insects while they allowed birds to eat and deposit seeds in other areas. These same milpas, assumed a huge role in Mexican gastronomic history, when their sides were fashioned into berms and then used as shallow ponds to culture fish or insects.

A “Three Sisters” mixed crop milpa

Labor and yield define maize’s role in Mexican food history and culture. Corn has one of the highest plant to harvest ratios of any crop, and required only two days a week’s labor to support a Mayan family of four. No sophisticated process or equipment was needed to harvest, grind or cook the derived staple and the grower was the final consumer. But the probable chance of discovery of the nixtalimization process is by far the most amazing element of the technology. Someone – Somewhere – Sometime found that when the raw fresh or dried corn kernel was boiled with lime ash or cooked in a limestone vessel, the outer hard shell or pericarp was much easier to remove. Not only did this discovery make it easier to process the product, but it also allowed the human metabolism to completely absorb the nutrients that are unavailable with the pericarp intact. This processed corn when combined with beans, chilies, fruits, or vegetables provided all the necessary human amino acids in a mostly meatless environment. This ground meal was then mixed with water to form a gruel or a beverage, served either hot or cold, or made into masa for tortillas and tamales that were easy to transport and consume. The ground toasted kernels when mixed with water made a beverage that flavored with chilies, herbs, beans, marigold leaves, roasted nuts, seeds, sweet potatoes, sweet maguey syrup, honey, agave or cocoa for the nobility.

Vegetables and corn stew along with tamales of maize, plantains, yucca, cassava, chia or amaranth seeds are commonplace in Mexican food history. The Mayans preferred tamales, either steamed or fire roasted, over tortillas and dined on insects or wild game when available. Corn was so esteemed that a baby’s umbilical cord was severed over a fresh ear of maize and a taste of masa was placed in your mouth at death. The Aztec creation myth tells us of the several attempts to create man all failing until on the fifth issue man was fed corn and lived. The Mayan Popol Vuh also chronicles several unsuccessful attempts that only ended when the gods mixed their own blood with masa to form the first man. The gist of both myths illustrates the importance of giving auto or honoree/victim blood back to the creation and corn gods pretty obvious. The people of both cultures lived in constant fear of the deities and their nobility but any Aztec could opt for suicide if he wished and respectfully wind up in a special heaven with a special goddess to welcome him.

The fast growing amaranth bush’s leaves, seeds, and flowers have an amazing 16% protein yield by weight, higher than wheat at 13% or rice at 7%. They can be added to stews or moles and the seeds are eaten raw, ground into flour for tamales and tortillas or popped and eaten like corn. When combined with sweet maguey syrup or honey and some ground annatto seeds or blood they produced a malleable product later shaped into effigies of various deities something like our chocolate Easter Bunnies. Pieces of these figures were distributed to audiences at religious rites so that they could vicariously take part in the blood rituals much like the Christians do with the communion of the transubstantiation. Because of this veiled specter of the Catholic ritual old world priests diligently tried to eliminate these cultural icons but they are still sold today by vendors in Mexico City as sweets called alegrias. Amaranth has become one of the new darlings of the sustainable agricultural school because of its easy cultivation and high protein content.

A seed meal called pinole was also made from the chia plant, that’s right, the same chia pet plant your aunt gave you for Christmas, a member of the sage family. This chia was, and still is, a dietary foundation for many of the rural poor of Mexico and eaten as a sliced sun-dried loaf, gruel or beverage flavored with fruits or herbs. The oil pressed from chia and amaranth seeds was the only oil mentioned in pre-Columbian food history and it was as a body emollient not to fry in. The annatto seed, called achiote in paste form, when crushed produces a bright red pigment that had a well-documented role in the blood/corn religion of the two cultures. The Spanish were quick to adopt the colorant as a substitute for saffron and today it still exists as a canon of Mexican cuisine as the ubiquitous “Spanish” yellow rice served at every pseudo Mexican restaurant.

Fermented beverages existed but getting drunk at anytime other than a sanctioned religious event could condemn the imbiber to summary capital punishment. Pulque made from corn was the common beverage for the poor with a more up scale beer or honey wine, made from the balche tree bark and the often psychotropic xtabentun honey derived from morning glories, reserved for the upper classes and was regularly served at drunken ceremonial reveries that could last up to four days. Mexican food history tell us of a blood ritual wine made from passion fruit, maguey, soursop and cherimoya that is still served in the Yucatan today but without the sacrifice. Cacao, served by the Mayans hot at the end of a meal, was the most esteemed beverage of the nobility and was often flavored with maguey syrup, vanilla or various flower petals. Cacao beans were so prized that they were used for currency and regularly counterfeited by replacing the real nibs with one made of clay. The process needed to turn cocoa beans into a beverage is another example, along with slacked corn and milpa farming technology, of indigenous inventiveness. To transform cacao into a beverage you must first remove the seeds, called nibs, from the pods and then ferment, cure, roast and finally powder them. The cocoa powder was then combined with water and poured from one vessel to another to create a foamy head much like an espresso drink. During religious rites the nobility and priests drank draughts of the brew laced with peyote, mescaline, marijuana or various other psychotropic hallucinogens.

A Spanish image of a woman pouring cocoa from a height to give it a frothy head

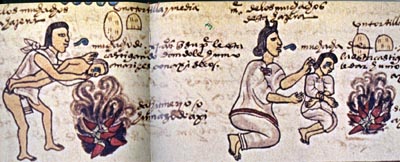

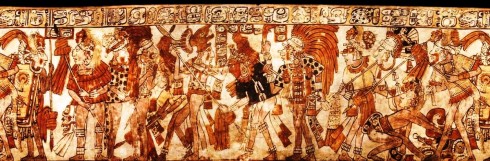

Meat, including human, was a rare treat for most and usually confined to the Mexican nobility, wealthy merchant or warrior class in any frequency. The human variety was savored only during religious rites held once every twenty days, after battles, to commemorate some new civil project or otherwise appease the Mayan gods for the successful planting and harvesting of crops. Both men and women tattooed their bodies with black copal [tree resin] which was also used for incense, and bathed at least once, if not more, a day.

The foreheads of the nobility’s newborns often underwent sometimes fatal elective surgery to form the elongated and flattened cranial shape commonly portrayed on temple walls and in surviving codices. Crossed eyes were also considered an affectation of wealth and beauty and infants were rigorously conditioned to achieve it. Wounds were sutured with human hair, willow bark, natures aspirin, was widely used as an analgesic, dental caries were filled with iron pyrite and damaged teeth often had crowns of jade and turquoise.

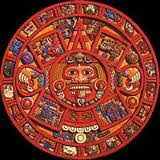

Extremely accurate calendars determined planting and harvesting cycles, foretold propitious times for military campaigns, religious rites, and the initiation of civic projects as well as the need for blood sacrifice. Both the Mayan and the Aztec calendars were composed of eighteen twenty day months each with its own prescribed ceremonial rites that entailed human sacrifice. Every 52 years the sun, the principle god, would exhaust its cosmic energy and it had to be replaced through massive human sacrifices. The concept of “0” was recognized and wheels were used for toys but not, since there were no beasts of burden, for transport. Recently Mayan hieroglyphics have been deciphered to reveal a combination of runes/glyphs and sounds that combine to form complete words not just concepts. Unfortunately Spanish priests destroyed most of the “heretical” codices, some dating from 300 BCE, when they began saving Mayan souls.

Recently Mayan hieroglyphics have been deciphered to reveal a combination of runes/glyphs and sounds that combine to form complete words not just concepts. Unfortunately Spanish priests destroyed most of the “heretical” codices, some dating from 300 BCE, when they began saving Mayan souls.

The later Mayans of the Yucatan traded with the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan in salt, obsidian, jade, cacao, feathers, pottery, copal, jaguar pelts, flints, cotton, honey, salted fish and smoked venison. The common Mayan wore a simple cotton dress or breech cloth while warriors regaled in quilted cotton armor so effective that many conquistadors and their war dogs adopted it. Trade for the rich was in barter or cacao beans while the poor lived in well fed poverty giving half of their crops and labor to the ruling classes and the state. At its apex the Mayan empire, of which an estimated only 1% has been discovered, consisted of 20 city states with a shared culture and religion. The empire was in severe decline by the time the Spanish arrived and the national diet had been reduced to only a shadow of what had been consumed earlier. Had the civilization not been in the throes of civil strife and famine history might have played out quite differently when the Spanish invaders made landfall.

The Aztecs were a group of city states bullied into a treaty called the triple alliance by the Mexica people, aka Mexicans, who spent 150 years building this allegiance into the most powerful state in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. Their massive civic, agricultural and scientific projects intimidated other city states who, in obeisance, paid tribute in cotton, cloth, food, precious metals, gems, stones, soldiers and sacrificial honorees as needed until Hernan Cortez, preceded and accompanied by measles and smallpox, arrived. The early inhabitants, dating from 1000 BCE, were hunters and gatherers using a broad spectrum of local plant sources that included early ancestors of corn as we know it. Yuca [cassava], plantains and yams were the primary Mexican food starch until corn became a cultivated crop in about 250 BCE.

Aztec Gods … read more, click here

This early Mexican vegetarian diet was supplemented with fresh water fish, shrimps, crickets, ants who had gorged themselves on marquey syrup, Axolotl salamanders, maguey worms and pocket gophers. A water bug, known as the axayacatl, was harvested, minced, enclosed in a corn husk or other leaf and then either fire roasted or steamed. Water worms and insect eggs were roasted together and then rolled up in a corn tortilla with a few chilies for a protein rich meal. One type of fresh water algae, known today as spirulina, was easy to cultivate and yielded 60% protein by weight. This algae was skimmed from the lakes, ponds and rivers then shaped into loafs which were dried in the sun and sliced like cheese or cold cuts. Cactus flowers, leaves, fruits, paddles and trunks were eaten in profusion and a mild alcoholic beverage, something like mezcal or pulque, was obtained by fermenting various parts of the cultivar. The nobility, priests and warriors, unlike the commoners, often dined on dog, turkey, venison, jungle game and imported dried fish.

The “Aztec” nobility quaffed their cocoa cold and it had even more cultural prestige because it had to be imported into the valley of Mexico. The Spanish quickly adopted it for its ability to assuage fatigue, displace hunger and prevent sleep. The Mexican, like the Mayan, bathed at least once a day and you can imagine their olfactory shock when they first met the Conquistadors who hadn’t bathed or changed clothes since they left Spain. Both Mayan and Aztec worshiped the ideal – perfect body like the Greeks, Persian, Romans and Americans and they loved personal adornment. Courtesan Mexican women painted their faces with yellow ochre, traced tattoo like patterns of their feet, hands and necks with copal, painted their unexposed breasts and stomachs, and dyed their longer the better hair with indigo to give it luster. Women often filed their teeth to points and men frequently had dental inlays of turquoise or jade. Pleasure girls wantonly stained their teeth with cochineal dye which the British later used to make their coats red. Chewing gum or chicle came in several varieties including asphalt, bitumen, or naturally secreted latex from the sapodilla. It was acceptable for young girls in public, at home for mature women and in the closet for grown men since it was considered effeminate. The Mexican favored the corn tortilla as a mainstay while the Mayan preferred tamales to transport food to their mouths. Mexican food has innumerable regional cooking styles all dependent on the local larder. If you were to compare a period Mexican shopping list with that of the same period European the Mesoamerican consumer would have had far more items that required a substantially larger grocery cart.

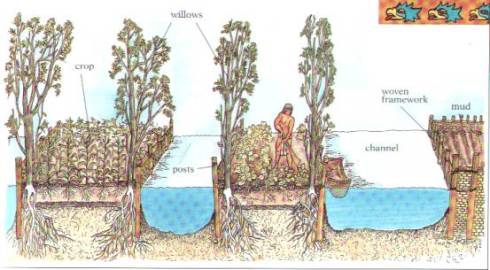

Mexican domination of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica owed much to the man-made islands, called chinampas, that surrounded the city-state of Tenochtitlan in the enormous lake Texcoco. These ingenious floating islands were constructed of woven reeds, fibers and rich lake bottom silt and were fertilized with bat and bird guano imported all the way from Peru and Baja, California. Human effluent, collected and stored in a fleet of canoe mounted outhouses that surrounded the city were nightly emptied on these patches of floating farmland enabling them to yield up to four crop rotations a year. When the sides were raised these chinampas became aquatic repositories where fish and insects were raised providing a constant, albeit insufficient, food source that was protected by an impressive irrigation and dike system. Daily caloric intakes for the citizens of Tenochtitlan are estimated to have ranged from 1400 for the poor to 2600 for the upper classes which helps to explain the difference in statue between the Mexican and their 1200 calorie a day Mayan counterparts. The massive irrigation systems of the Mexican meant that a hundred families could be fed by farming just 86 hectares while it took the Mayans 1200 hectares to feed the same number using the more primitive slash and burn technology.

Worship of the Mesoamerican pantheon, 90% of whom were connected to crops, water and the minutiae of corn products, processes and production, required the daily individual or occasional public display of blood-letting. The legends of both cultures stated that, since the gods had used their own blood mixed with corn to create man, it was man’s responsibility to provide a constant resupply through tribute in return. Without this blood payment and the constant genuflective deference to the gods the world would end and this concept made for a lot of paranoid and depressed natives. Corn was highly revered and just as a Chinese mother taught her daughter to prepare and venerate rice so a Mexican mom imparted the nuances of making masa. Masa was so sacred that you cajoled and blew on an ear before subjecting it to fire so it wouldn’t fear the heat and if you dropped an ear or kernel you would reverently retrieve it and clean it before use. What an affront it must have been for the Aztecs when they ritually offered some of this cultural icon to the unwashed Conquistadores who quickly threw it on the ground for their livestock.

Sacrificial cannibalism was most certainly practiced by the Mexican elite who, many authorities now think, may have surreptitiously substituted a turkey thigh for a human one. The number of human sacrifices, thought to be about 10k for an average year, will always remain in flux. But around the year 1450, after several years of famine, the Aztec rulers decided that it would be easier to decrease the population than increase agricultural production and so they ramped up their offering to the gods. Human sacrifices now took on a new perspective and the ritual eaters would add a little salt and a few chilies to those being wrapped in tortillas and eaten. These same honored dining guests would appease the gods daily by using maguey thorns to pierce their own bodies and proffer their own blood as absolutions. A brief respite from this daily blood-letting was practiced when Aztecs fasted, and they all did no matter what their age, sex or social status, because their blood was weakened from the rigors of their fast and therefore not suitable for the gods.

Every fifty-two cycles the Mexican priests would fast for an entire year eating only two ounces of masa a day, although they were allowed a once a month pig out, to prepare for the upcoming sun sacrifice ritual that would ensure the worlds continuation for another 52 years. During this ritual, just before sunrise, a male virgin had his chest opened and his still pulsating heart was severed and offered to the sun god who was often known as Huitzilopochtli. When the sun began to rise a fire was started in the honorees chest cavity and its embers where spread throughout the city to rekindle the city’s hearths that had been extinguished the day before. A particularly notable ceremony was recorded during 1487 when over a four-day period some 15 to 85 thousand sacrifices occurred to commemorate the completion of the sun temple in Mexico City. If some event of peace time portent required a large number of sacrifices a war of flowers was agreed to by the Mexica and one or more, depending on the number of honorees needed, of their vassal states. The sole purpose of this war was the capture of sacrificial honorees to be offered up to the gods for the benefit of the empire. As many citizens as possible participated in the ritual either by watching, guarding, feeding, bathing or servicing the honorees in some way before sacrificial Sunday or by butchering, cooking, dispensing or cleaning up after the event as this was the Mexican food equivalent of Super Bowl tailgating.

The Mexicans thought of themselves as heirs to the Toltec culture and therefore socially, morally, spiritually and physically superior to any of their vassal subjects. To be born a male in Tenochtitlan was to be born a warrior: both commoner and noble were expected to show valor in battle. Only rarely could an outsider advance to the level of citizen with its rank, privilege and protection much like becoming a Roman. A constant flow of tribute and commodities came into Mexico city daily to supply the more than 300,000 residents and artisans, more than the Venice or Madrid of the same period, with the accoutrements of everyday Mexican life. The central market brought some 60,000 merchants, peddlers, ambassadors, farmers and customers together in a 24/7 procession in and out of the city. The high population density, fear of numerous gods, nobles, crop failures, war and possible selection for sacrifice made illicit drug use and drinking rampant even if it was forbidden at all times except for festivals. During sanctioned festivals everyone, including children, was encouraged to imbibe to help channel any manifest sacred forces. But social mores forbade unsanctioned drinking and drug use, outside of any religious context, as it was considered a disruptive and endangering force both to the Aztec culture and the individual.

Drink was tolerated with a smile for those elders over 70 but for particularly younger and disruptive drunks summary execution was not unknown. The offender was taken to the marketplace and publicly strangled, stoned or clubbed to death becoming an added attraction to a day of shopping. Warriors, priests and pleasure girls would often abuse their positions by roaming the neighborhoods extorting residents for a few cacao beans or perhaps a bowl of maize and bean soup to be left alone. Pulque, the fermented honey water of the century or maguey plant, was the drink of choice among the Mexican and was often fortified with jimson weed, marijuana or morning glory seeds which transformed it into the euphemistic “milk of the gods”. This psychedelic brew was given to sacrificial gladiators before their bouts and it was also used to lubricate the priests ritual obsidian knives before their lethal incisions. The same mildly hallucinogenic punch was given to children at their first festival, although I suspect from experience, in relatively small amounts …. just enough to make the lights refract and impress the little darlings with enough shock and awe to last a lifetime.

![A paste of this flower and it seeds, Rivea corymbosa, called Oliliuqui in Nahuatl [Aztec] was rubber on warriors before battle for an psychedelic rush](https://mexicanfood1.files.wordpress.com/2010/10/rivea_corymbosa.jpg?w=490&h=392)

A paste of this flower and it seeds, called Oliliuqui in Nahuatl [Aztec] was rubber on warriors before battle for a psychedelic rush

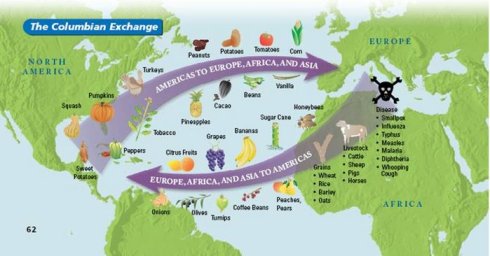

By 1492 the combined population estimates of Spain and Portugal had reached about 10 million while Central Mexico had a census estimated somewhere between 25 and 112 million. The Atlantic crossing and the meeting of old and new world cultures is arguably the most important event in humankinds history. These meeting of the two worlds resulted in an exchange of genes, fauna and knowledge that forever changed the course of the world. Previously Europe’s cultural, monetary and technological impetus had originated in the East and had the Old and New world not hookup the stagnation of the middle ages would have probably continued. The new trade route brought gold and silver into the cash strapped European economy and scores of new cultivars to its starving peasant classes that were dependent on the commerce of the East. Where explorers and traders go … so does the biota and memes of the connecting cultures whether they’re welcome or not. Cortez and his posse were stunned to see few fallow fields and ever more amazed when they discovered that maize required no draught animals or plows and was easily fertilized by amending the soil with local animal and human wastes. The fields the conquistadors saw in the new world were strikingly different from those back in Spain that were so sapped of nutrients that it was hard to coax one harvest a year out of them to assuage the almost constant state of famine. It took an Aztec farmer just three months a year to produce enough food to feed two families of four. This gave the locals plenty of time to make babies, smoke marijuana and work on massive civil projects all the while supporting a huge noble, warrior, priest and artisan class that impacted the world.

Today’s Mexican food has both Spanish and Portuguese cuisines as its underpinnings and they in turn were influenced by their Roman and Arab precursors. The Portuguese were the first to traverse the Cape of Good Hope, they discovered Brazil and plotted a sea course to the spices of the East. They invented the Caravel, a ship that could sail against the wind, and Vasco de Gama used it to bring cloves, nutmeg, pepper, rice, coffee, tea and fava beans to the new world. Anthropologists blame De Soto’s Florida introduction of pigs for the almost complete annihilation of Americans North Atlantic cultures. The argument contends that any disease his crew may have been infected with would have run its course well before they reached landfall while just one errant porcine could have infected the local deer, turkey or squirrel population. The Aztecs of course owe much of their thinning to Hernan Cortez’s introduction of the smallpox and measles vectors into a culture that had absolutely no immunity.

Aztec food was either boiled, fire roasted or steamed on a rack, very much like the Chinese, in an earthenware pot called as olla while stews or moles were cooked in a casserole called a cazuela that was placed in or suspended over an open fire. Early Mexica cuisine was historically an amalgam of indigenous trade goods, gods and foodstuffs while post Colombian Mesoamerica quickly adopted the cultivars and animal proteins of the Old World. A huge indigenous population, even after suffering from a cataclysmic bout of imported disease, had enough survivors to fuse Spanish imports with native inputs. On the smaller islands of the Caribbean initial contact often destroyed the entire population and only Spanish cuisine remained usually renamed in the native tongue. Frying was unknown in the New World, since the Mexica had only limited oils from seeds, and the process had to wait for Spanish livestock and technology to turn animal fats into lard, milk and cheese. Today’s taco, quesadilla, tostada or torta would be hard to imagine without cheese and sour cream even though they are a purely US affectation. Vegetables and fruits brought by the invaders included onions, garlic, bananas, carrots, turnips, eggplant, lentils, peaches, melons, figs, cherries, oranges, limes, wheat, nuts, citrus and dried fruits. Many of the products the Spanish took home later returned as the culinary baggage of other cuisines rejoining the existent pool of indigenous and Iberian foodstuffs to become the archetypical dishes featured in today’s Mexican food. We don’t know how fast these Spanish imports were assimilated and many food historians think that the pre-Columbian diet persisted well into the twentieth century due to the prohibitive costs of beef and wheat in the rural areas of the hinterland. Pulque and achiote paste are two examples that have remained for centuries although the beverage is no longer laced with psilocybin and annatto paste no longer masquerades as blood.

Frugality is a trait that is evidenced throughout Mexican cuisine and the beverage called horchata, made from the water used to wash rice before cooking and then mixed with sugar, and sometimes a little cinnamon, is just one of the tasty examples. Pork, lamb and goat were quickly integrated as was beef, since it was only valued for its exported hides, and it appeared on almost everyone’s plate during the colonial period. But massive cattle herds soon exhausted the grasslands and beef became a luxury item only for the wealthy until it experienced broad cultural resurgence during the French period. Wheat and animal protein were the cornerstones of Nuevo Spanish Cuisine and priests devoted their efforts not only to converting and saving souls but also reshaping the locals’ dependency on corn and other cultivars that could be shaped into graven blood images. This task wasn’t easy since 80% of the Aztec caloric consumption before modern time came from corn and amaranth. Wheat was a given since it was the only grain you could use for communion wafers; but unfortunately it requires lots of irrigation, has really low yields as compared to maize and suffers from many plant diseases precluding it from a favored cultivar for subsistence farmers. Furthermore early Mexican food did not use above ground ovens and so the technology of baking and flour milling had to be taught before wheat became a component in the Mexican food diet. When the locals were forced to work at Spanish wheat farms they received compensation in the form of baked bread so the staple gradually made inroads into the diet. Eventually during the French period many Gallic bakeries opened and by the end of the century 40 million pounds of bread a year was being sold in Mexico City and today the country is well-known for its 1500 types of savory and sweet baked goods.

The initial inoculations of old world cultivars and animal protein raised the nutritional bar for the locals until the barter system morphed into a cash one in the middle seventieth century forcing dietary well being to levels lower than those of a century earlier. The Mexica left behind a rich culinary legacy of recipes, recorded by the invading Spanish, many of which exist in their original form today. A lack of communication and transportation kept regional dishes tethered to their place of origin and when recipes did travel they were often labeled “in the mule drivers style” since it was these journeyers who spread the latest dish or cultivar. This regionalism also slowed the spread of Old World foods into the interior where most Mexicans relied on the centuries old diet of tortillas, beans and a sizable smattering of the more than 90 available chilies. Early Pre-Columbian Mexican food had an amazing depth and diversity illustrated by the 300 different menu choices offered to Motechuhzoma daily while conversely the many brandies, tequilas and mescals of Mexico owe their existence to the imported distillation techniques of the Spanish via the Arabs.

When the Spanish arrived they brought Roman, Sephardic and Moorish culinary remnants but no women. They soon hooked up with the native girls who blended not only genes but imported foodstuffs into the local recipes and the babies they always produced. Since there was no wheat for the new arrivals the local cooks incorporated the imported fats and proteins into the already existing masa base which evolved into the meat, cheese and chili dishes we call Mexican food today. In the middle of the seventeenth century when women of the Spanish aristocracy arrived as brides, or in pursuit of proper husbands, they would take up residence in convents where the good sisters could supervise and protect them. There wasn’t a lot to do in these church established hostels so the educated senoritas and their hired Indian maids would while away their time creating the archetypical dishes that have become the benchmarks of Mexican food. So spices from the old world were combined with those from the new and inspired the birth place of the wheat tortilla, a still shunned and derided item to many, and the redolent combination of imported coriander, cinnamon and cacao fused with the local turkey to create mole.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the French were at their zenith and Gallic culture was the one to emulate. When Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian assumed the Mexican throne as emperor, although the US failed to recognize him, he brought along an entourage of French cooks and fashion to his new court in Mexico City. Soon French gowns, cream soups, mustard sauce, crusty breads and Parisian pastries became features of the transported French Empire and pasta machines were hard at work in Mexico City

Some time later when British miners came to Mexico they brought along the hand held meat pie called the Cornish pastie that later morphed into the empanada. A century later Lebanese immigrants saw their spit roasted lamb and pita bread sandwiches evolve into tacos al pastor.

When the Mexican army came to fight the war against the invading US they were accompanied by women camp followers who cooked, washed and serviced the troops in the campaign against the Gringos. When the army was defeated many of these Mexican women decided to stay with their sisters in the newly established state of Texas where they set up shops in the town square of San Antonio serving a fusion dish of meat, beans and chilies and were soon being called the chili queens by the Texicans.

By the beginnings of the twentieth century chili parlors had become the culinary darlings of the day and everyone who was anyone had a recipe published in the print media of the period. In 1892 a German immigrant named Gebhardt began drying and blending chilies and started marketing his product as “chili powder”, if I brought anything other than it home in 1950’s Palo Alto, Ca. my grandmother Avis would make me take return it and bring back “the real stuff”, and this premade spice helped put the construct into every American kitchen. Gebhardt’s, now owned by ConAgra, still makes chili powder and frozen tamales.

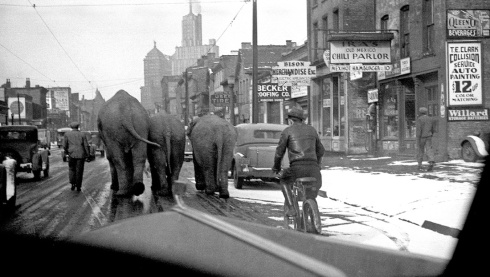

1930’s Buffalo N.Y. notice “IRA”S” chili parlor to the right with 10 cent burgers. The circus comes to town. 10 cent bowl of chili with all the crackers you could eat, or tortillas towards the south, fed many a depression era diner.

You may or may not be familiar with the refrain “hot tamale, hot tamales, get your hot tamales here” it’s the stuff of childhood cartoons and Hollywood baseball movies. Well imagine the shout out having a decidedly Italian accent and it’s what you’d hear on the streets of Los Angeles in the 1880’s when Mediterranean immigrants controlled the Mexican tamale market hawking their product from push carts.

And of course there’s tamale pie, a famous comfort food birthed around 1911, with the modern-day versions known as “helper” or Chili Mac that graces the Carrara marble dining islands of many a suburban McMansion in both convenience and homemade guises. Blue corn tortillas, cactus pears, jicama and corn smut were the darlings of the 70’s and salsa is now more popular than ketchup. Pseudo tacos, burritos, tostadas and other handheld Franken foods with ersatz names created by Taco Bell, whose CEO says “we never call our food Mexican”, sell by the millions. Mexican food is succumbing to the onslaughts of the great North American Alimentary Apocalypse lead by processed foods from Wal-Mart, white bread from Bimbo, Mountain Dew from Pepsi and KFC from Yum Brands. Modern day Aztecs now consume more Coca Cola then their North American cousins and many younger Mexicans don’t like chili inspired dishes because they’re too spicy. The hand-held masa dishes of the past are being replaced by the triple whopper, pepperoni pizones and the super sized portions of the Gringo … too bad.

Here’s a few videos …

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_okQ7CJiNoU

http://dsc.discovery.com/tv-shows/other-shows/videos/discovery-atlas-mexico-food.htm